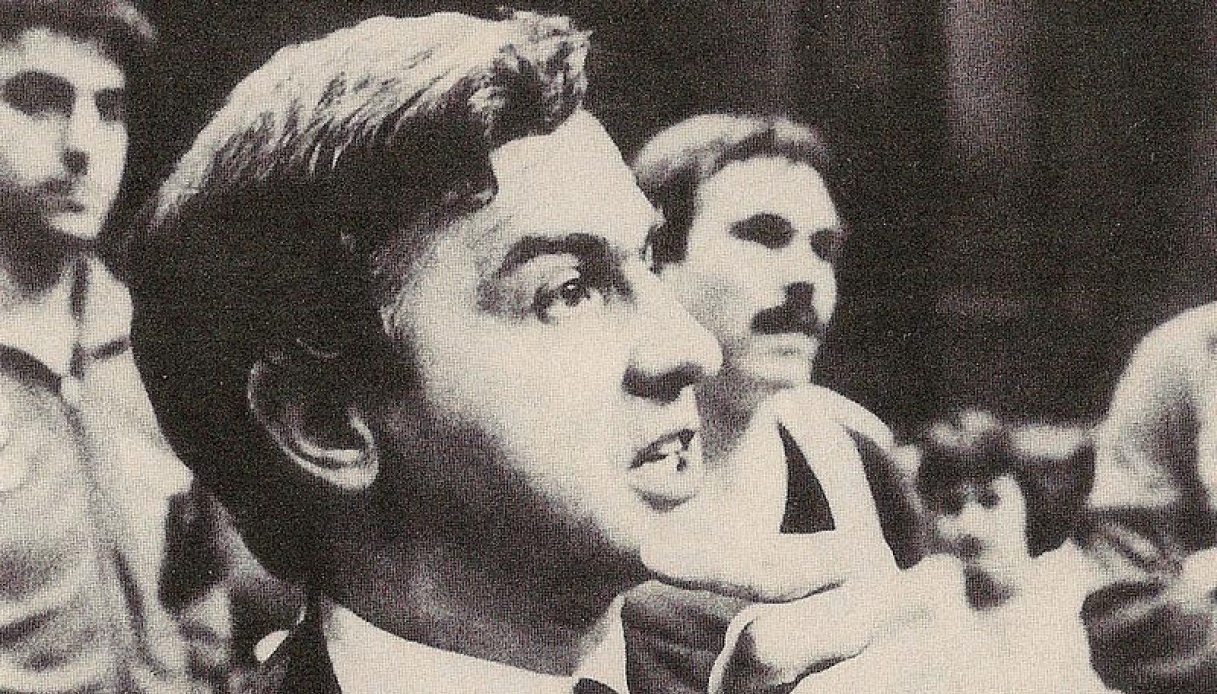

Franco Casalini, Olimpia Milano’s remembrance.

The memory of Franco Casalini

Olimpia Milano paid tribute to Franco Casalini with a lengthy message of condolence on its official website.

“Franco Casalini has left us. He was only 70 years old, born on January 1, 1952 in Milan. He leaves behind his brother Paolo. He was not married, had no children, for Franco Casalini Olimpia was synonymous with family, that family he joined in 1972 when he was only 20 years old. His years at Olimpia, first in youth (with four titles), then as an assistant to the first team, then Dan Peterson’s historic right-hand man and finally head coach, were the most intense in the club’s history. As head coach, Franco Casalini – who is a member of the club’s Hall of Fame, of which he was one of the original selectors – won the 1988 Champions Cup when he was only 36 years old (he was the youngest Italian coach to win it) and the 1989 Scudetto, the one he won in Livorno. In addition, he had led the team as a rookie to victory in the 1987 Intercontinental Cup in Milan. “He was in love with Olimpia and what it represented; he was a loyal friend and comrade. If we then go and look at the wins, how many can say they did better?” said Peterson yesterday.

It was Cesare Rubini who brought him to Simmenthal in 1972 when he was 20 years old. He hired him without offering him big money, just a lot of hard work and honor. He left his home company, Social OSA, and landed in Via Caltanissetta. In the following years Olimpia became his de facto home: endless days spent in the gym, working on fundamentals, for an ideal. And when the weekend came and there was no training, the days were spent roaming the Milanese hinterland, looking for players, ideas, information, or just because that was the life he, and others like him, had chosen for themselves. In 1977, Casalini was 25 years old when he became Pippo Faina’s assistant in Mike D’Antoni’s first year at Olimpia. The point guard was older than the assistant coach, so when he became the team’s head coach Casalini considered himself a “Co-coach” or a kind of “primus inter pares.”

In 1978, he became the historical assistant to Coach Dan Peterson (the other was Guglielmo Roggiani who unfortunately left us as well). As an assistant, he won four championships, a Champions Cup, and a Korac Cup. With the wins, Peterson became more and more of a character, harder and harder to contain within the confines of basketball. Then he had this idea that he didn’t want to coach too long. Every year when the season was over, he would say he wanted to quit. And in those days there was no doubt who would be his heir. “Every year Dr. Gabetti (president-owner of Olimpia in those days – ed.) would call me and say that Peterson was going to quit by offering me to become head coach – Casalini himself recounted a few years ago – But after a few days the counter-call would come punctually, it was him or our general manager Toni Cappellari: Peterson had decided to continue. It was never a surprise: I knew he would never retire before winning the Champions Cup, and I as an assistant was happy that he would continue coaching.”

The Champion’s Cup was Olimpia’s fixation, at least since 1983 when in Grenoble he lost the final-derby to Cantù in a nail-biting and confusing final. “The same phone call came to me, however, in 1987 after winning the Champions Cup. When Gabetti made the ritual phone call to me, I went home wondering if I would get his counter call again. Instead it was Peterson who called me,” Franco recounted. The coach was lapidary: “Hi Franco, you’re on your own now….”

Just so he would quickly understand what was in store for him, Olimpia’s first engagement in the new era was the Intercontinental Cup, in Milan by the way. “We were the organizers, we were coming from the Grand Slam, we were overachievers, and we had to win,” Casalini said, retracing the steps of his career. Not exactly a soft landing. Then the debut against Barcelona. Candido Sibilio, a phenomenal small forward, was there. Olimpia lost the first game, but then never lost again and won the trophy: “Winning that trophy gave me a huge relief. Honestly, I was feeling the pressure of the debut,” he had to say.

There were some historic moves in Olimpia’s history. Peterson is remembered for marking Larry Wright, 1.85, with Vittorio Gallinari, 2.08. But Casalini also had his own anecdote. In 1988, Milan’s problem was small wing marking, a flaw that would cost them the Scudetto against Darren Daye’s Scavolini. But in the Champions Cup, the problem Candido Sibilio pointed out at the beginning of the season recurred as such in the Final Four in Ghent. The semifinal was against Aris Thessaloniki. The threat posed by Nick Galis and Panagiotis Giannakis was obvious, but Casalini feared Serbian bomber Slobodan Subotic. “It occurred to me one night-to entrust him to Meneghin. Maybe because I knew he was such a great player who could do everything. I used to say that he did not play point guard by his own choice, but he could do it. I did not consider myself a real coach, but a first among equals. When I decided to have Meneghin mark Subotic, I consulted with my peers, with Dino and Mike D’Antoni, as well as with Toni Cappellari. We met for lunch to discuss it. They hadn’t even set the table for us. I asked Dino if he felt up to it and he said yes. D’Antoni said it was a good idea. In 12 seconds we had decided,” was his account. Olimpia defeated Aris, then also Maccabi, and won the Champions Cup.

With D’Antoni and Meneghin, the other star was obviously Bob McAdoo. Casalini knew him better than anyone, because he had coached him three years as head coach in Milan, one as an assistant, and then also had him in Forlì. A year after the Champions Cup, Casalini also won the Scudetto, in the famous final in Livorno, the one with McAdoo’s dive. “It’s a game I remember as being shrouded in a haze, I don’t remember exactly how it unfolded. We were used to seeing things out of the ordinary, but that dive we never even imagined, because it was not part of him, his repertoire, it was certainly not his workhorse. He had made decisive stops, grabbed decisive rebounds, but something like that in the half-court, a five- or six-meter flight, which might as well have been pointless, I wondered how it could have come to a 38-year-old player’s mind,” was his account.

Casalini stayed at Olimpia 18 years. He left after the 1989/90 season, when Mike D’Antoni after retiring immediately became the club’s head coach. “Those were the decisive years of my life, without those 18 years I would not be the same person, for me Olimpia is not my home, it is my life,” he said. Franco Casalini we mourn him today, we will always mourn him.”